Línea 25:

Línea 25: ;Punto B:

;Punto B:

<center><math>\overrightarrow{OB}=R\vec{\imath}</math>{{qquad}}{{qquad}}<math>\vec{v}^B = \vec{v}^O +\vec{\omega}\times\overrightarrow{OB}=v_0\vec{\imath}+\left|\begin{matrix}\vec{\imath} & \vec{\jmath} & \vec{k} \\ 0 & 0 & -v_0/R \\ R & 0 & 0 \end{matrix}\right| = v_0(\vec{\imath}-\vec{\jmath})</math></center>

<center><math>\overrightarrow{OB}=R\vec{\imath}\,\,; </math>{{qquad}}{{qquad}}<math>\vec{v}^B = \vec{v}^O +\vec{\omega}\times\overrightarrow{OB}=v_0\vec{\imath}+\left|\begin{matrix}\vec{\imath} & \vec{\jmath} & \vec{k} \\ 0 & 0 & -v_0/R \\ R & 0 & 0 \end{matrix}\right| = v_0(\vec{\imath}-\vec{\jmath})</math></center>

;Punto C:

;Punto C:

<center><math>\overrightarrow{OC}=R\vec{\jmath}</math>{{qquad}}{{qquad}}<math>\vec{v}^C = \vec{v}^O +\vec{\omega}\times\overrightarrow{OC}=v_0\vec{\imath}+\left|\begin{matrix}\vec{\imath} & \vec{\jmath} & \vec{k} \\ 0 & 0 & -v_0/R \\ 0 & R & 0 \end{matrix}\right| = 2v_0\vec{\imath}</math></center>

<center><math>\overrightarrow{OC}=R\vec{\jmath}\,\,; </math>{{qquad}}{{qquad}}<math>\vec{v}^C = \vec{v}^O +\vec{\omega}\times\overrightarrow{OC}=v_0\vec{\imath}+\left|\begin{matrix}\vec{\imath} & \vec{\jmath} & \vec{k} \\ 0 & 0 & -v_0/R \\ 0 & R & 0 \end{matrix}\right| = 2v_0\vec{\imath}</math></center>

;Punto D:

;Punto D:

<center><math>\overrightarrow{OB}=-R\vec{\imath}</math>{{qquad}}{{qquad}}<math>\vec{v}^D = \vec{v}^O +\vec{\omega}\times\overrightarrow{OD}=v_0\vec{\imath}+\left|\begin{matrix}\vec{\imath} & \vec{\jmath} & \vec{k} \\ 0 & 0 & -v_0/R \\ -R & 0 & 0 \end{matrix}\right| = v_0(\vec{\imath}+\vec{\jmath})</math></center>

<center><math>\overrightarrow{OD }=-R\vec{\imath}\,\,; </math>{{qquad}}{{qquad}}<math>\vec{v}^D = \vec{v}^O +\vec{\omega}\times\overrightarrow{OD}=v_0\vec{\imath}+\left|\begin{matrix}\vec{\imath} & \vec{\jmath} & \vec{k} \\ 0 & 0 & -v_0/R \\ -R & 0 & 0 \end{matrix}\right| = v_0(\vec{\imath}+\vec{\jmath})</math></center>

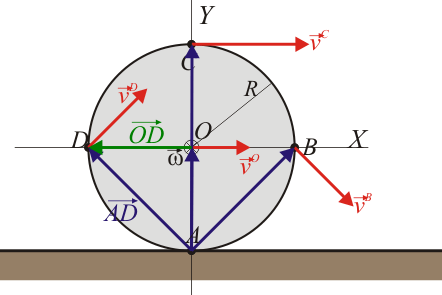

Obtenemos que el punto de contacto con el suelo posee velocidad instantánea nula, mientras que el punto superior posee velocidad doble a la de avance de la rueda.

Obtenemos que el punto de contacto con el suelo posee velocidad instantánea nula, mientras que el punto superior posee velocidad doble a la de avance de la rueda.

Revisión del 11:47 12 ene 2024

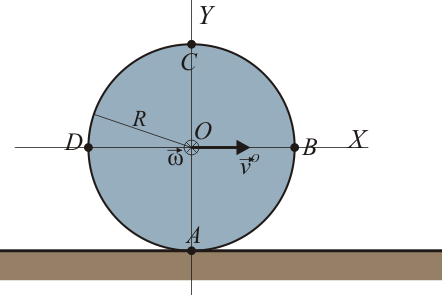

Enunciado La rodadura permanente de un disco de radio

R

{\displaystyle R}

v

→

P

=

v

→

O

+

ω

→

×

O

P

→

;

v

→

O

=

v

0

ı

→

;

ω

→

=

−

v

0

R

k

→

{\displaystyle {\vec {v}}^{P}={\vec {v}}^{O}+{\vec {\omega }}\times {\overrightarrow {OP}}\,\,;\qquad {\vec {v}}^{O}=v_{0}{\vec {\imath }}\,\,;\qquad {\vec {\omega }}=-{\frac {v_{0}}{R}}{\vec {k}}}

donde la superficie horizontal se encuentra en

y

=

−

R

{\displaystyle y=-R}

Determine, para un instante dado, la velocidades de los puntos A, B, C y D situados en los cuatro cuadrantes del disco.

Suponiendo

v

0

=

c

t

e

{\displaystyle v_{0}=\mathrm {cte} \,}

Velocidades Para cada uno de los puntos, basta aplicar la fórmula correspondiente

Punto A

Su vector de posición relativa es

O

A

→

=

−

R

ȷ

→

{\displaystyle {\overrightarrow {OA}}=-R{\vec {\jmath }}}

por lo que su velocidad vale

v

→

A

=

v

→

O

+

ω

→

×

O

A

→

=

v

0

ı

→

+

|

ı

→

ȷ

→

k

→

0

0

−

v

0

/

R

0

−

R

0

|

=

0

→

{\displaystyle {\vec {v}}^{A}={\vec {v}}^{O}+{\vec {\omega }}\times {\overrightarrow {OA}}=v_{0}{\vec {\imath }}+\left|{\begin{matrix}{\vec {\imath }}&{\vec {\jmath }}&{\vec {k}}\\0&0&-v_{0}/R\\0&-R&0\end{matrix}}\right|={\vec {0}}}

Punto B

O

B

→

=

R

ı

→

;

{\displaystyle {\overrightarrow {OB}}=R{\vec {\imath }}\,\,;}

v

→

B

=

v

→

O

+

ω

→

×

O

B

→

=

v

0

ı

→

+

|

ı

→

ȷ

→

k

→

0

0

−

v

0

/

R

R

0

0

|

=

v

0

(

ı

→

−

ȷ

→

)

{\displaystyle {\vec {v}}^{B}={\vec {v}}^{O}+{\vec {\omega }}\times {\overrightarrow {OB}}=v_{0}{\vec {\imath }}+\left|{\begin{matrix}{\vec {\imath }}&{\vec {\jmath }}&{\vec {k}}\\0&0&-v_{0}/R\\R&0&0\end{matrix}}\right|=v_{0}({\vec {\imath }}-{\vec {\jmath }})}

Punto C

O

C

→

=

R

ȷ

→

;

{\displaystyle {\overrightarrow {OC}}=R{\vec {\jmath }}\,\,;}

v

→

C

=

v

→

O

+

ω

→

×

O

C

→

=

v

0

ı

→

+

|

ı

→

ȷ

→

k

→

0

0

−

v

0

/

R

0

R

0

|

=

2

v

0

ı

→

{\displaystyle {\vec {v}}^{C}={\vec {v}}^{O}+{\vec {\omega }}\times {\overrightarrow {OC}}=v_{0}{\vec {\imath }}+\left|{\begin{matrix}{\vec {\imath }}&{\vec {\jmath }}&{\vec {k}}\\0&0&-v_{0}/R\\0&R&0\end{matrix}}\right|=2v_{0}{\vec {\imath }}}

Punto D

O

D

→

=

−

R

ı

→

;

{\displaystyle {\overrightarrow {OD}}=-R{\vec {\imath }}\,\,;}

v

→

D

=

v

→

O

+

ω

→

×

O

D

→

=

v

0

ı

→

+

|

ı

→

ȷ

→

k

→

0

0

−

v

0

/

R

−

R

0

0

|

=

v

0

(

ı

→

+

ȷ

→

)

{\displaystyle {\vec {v}}^{D}={\vec {v}}^{O}+{\vec {\omega }}\times {\overrightarrow {OD}}=v_{0}{\vec {\imath }}+\left|{\begin{matrix}{\vec {\imath }}&{\vec {\jmath }}&{\vec {k}}\\0&0&-v_{0}/R\\-R&0&0\end{matrix}}\right|=v_{0}({\vec {\imath }}+{\vec {\jmath }})}

Obtenemos que el punto de contacto con el suelo posee velocidad instantánea nula, mientras que el punto superior posee velocidad doble a la de avance de la rueda.

Las velocidades de los puntos O, B, C y D son perpendiculares al vector de posición relativo al punto A, como corresponde a que este se encuentre en el eje instantáneo de rotación:

v

→

P

=

v

→

A

⏞

=

0

→

+

ω

→

×

A

P

→

=

ω

→

×

A

P

→

⊥

A

P

→

{\displaystyle {\vec {v}}^{P}=\overbrace {{\vec {v}}^{A}} ^{={\vec {0}}}+{\vec {\omega }}\times {\overrightarrow {AP}}={\vec {\omega }}\times {\overrightarrow {AP}}\perp {\overrightarrow {AP}}}

Aceleraciones La expresión general del campo de aceleraciones es

a

→

P

=

a

→

O

+

α

→

×

O

P

→

+

ω

→

×

(

ω

→

×

O

P

→

)

{\displaystyle {\vec {a}}^{P}={\vec {a}}^{O}+{\vec {\alpha }}\times {\overrightarrow {OP}}+{\vec {\omega }}\times ({\vec {\omega }}\times {\overrightarrow {OP}})}

En este caso tenemos que la velocidad del punto O es constante, por lo que

a

→

O

=

d

v

→

O

d

t

=

d

v

0

d

t

ı

→

=

0

→

{\displaystyle {\vec {a}}^{O}={\frac {\mathrm {d} {\vec {v}}^{O}}{\mathrm {d} t}}={\frac {\mathrm {d} v_{0}}{\mathrm {d} t}}{\vec {\imath }}={\vec {0}}}

También es nula la aceleración angular

α

→

=

d

ω

→

d

t

=

0

→

{\displaystyle {\vec {\alpha }}={\frac {\mathrm {d} {\vec {\omega }}}{\mathrm {d} t}}={\vec {0}}}

lo que nos deja con

a

→

P

=

ω

→

×

(

ω

→

×

O

P

→

)

{\displaystyle {\vec {a}}^{P}={\vec {\omega }}\times ({\vec {\omega }}\times {\overrightarrow {OP}})}

Desarrollando el doble producto vectorial

a

→

P

=

(

ω

→

⋅

O

P

→

)

ω

→

−

ω

2

O

P

→

{\displaystyle {\vec {a}}^{P}=({\vec {\omega }}\cdot {\overrightarrow {OP}}){\vec {\omega }}-\omega ^{2}{\overrightarrow {OP}}}

Para los cuatro puntos del enunciado, el vector de posición relativo al punto O está contenido en el plano OXY y es por tanto perpendicular a la velocidad angular, con lo que la aceleración de cada uno se reduce a

a

→

P

=

−

ω

2

O

P

→

=

−

v

0

2

R

2

O

P

→

{\displaystyle {\vec {a}}^{P}=-\omega ^{2}{\overrightarrow {OP}}=-{\frac {v_{0}^{2}}{R^{2}}}{\overrightarrow {OP}}}

En los cuatro casos resulta radial y hacia adentro del disco, lo que nos da las cuatro aceleraciones

a

→

A

=

v

0

2

R

ȷ

→

{\displaystyle {\vec {a}}^{A}={\frac {v_{0}^{2}}{R}}{\vec {\jmath }}}

a

→

B

=

−

v

0

2

R

ı

→

{\displaystyle {\vec {a}}^{B}=-{\frac {v_{0}^{2}}{R}}{\vec {\imath }}}

a

→

C

=

−

v

0

2

R

ȷ

→

{\displaystyle {\vec {a}}^{C}=-{\frac {v_{0}^{2}}{R}}{\vec {\jmath }}}

a

→

D

=

v

0

2

R

ı

→

{\displaystyle {\vec {a}}^{D}={\frac {v_{0}^{2}}{R}}{\vec {\imath }}}